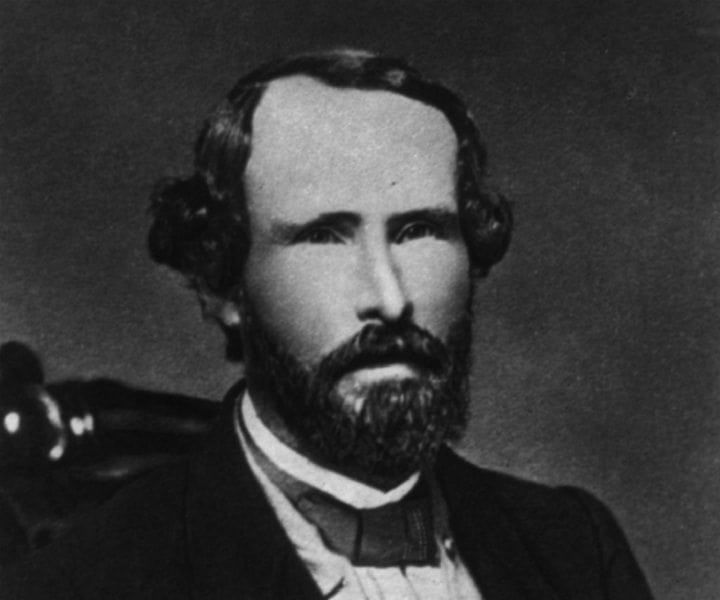

If you are familiar with US history, you probably know that the Monticello estate in Virginia used to be the plantation property of Thomas Jefferson. It is now thought to be a national landmark that both locals and tourists alike visit! There has been a lot of documentation of the place, but we doubt that you know about the secrets recently discovered on the property. Thanks to the efforts made by and historians have put in a lot of work towards this. With the new information available, we can now learn more about the 3rd President of the United States’ life. Are you ready to learn more about this Founding Father?

The Monticello Plantation Is Full Of Secrets About 3rd US President Thomas Jefferson

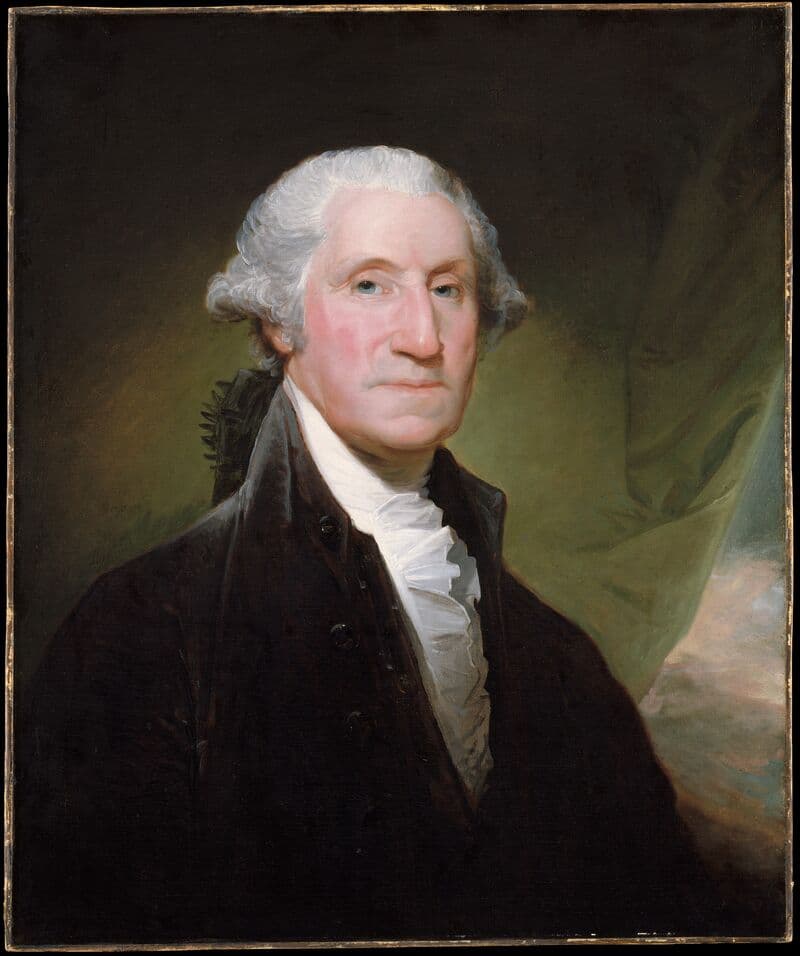

A Presidential Property

Thomas Jefferson went on to become the third person to hold the President of the United States position. Before he started living in the White House, he lived in the Monticello plantation in Virginia. Located in Charlottesville, its construction started in 1768. It is now deemed a national landmark. In case you were wondering, its name means “Little Mountain” in Italian. The main house of the historical estate even appears on the back of the nickel! While it was constructed a couple of centuries ago, it was recently discovered that the Monticello had been hiding a mystery all this time.

The Monticello Mystery

The Monticello Mystery

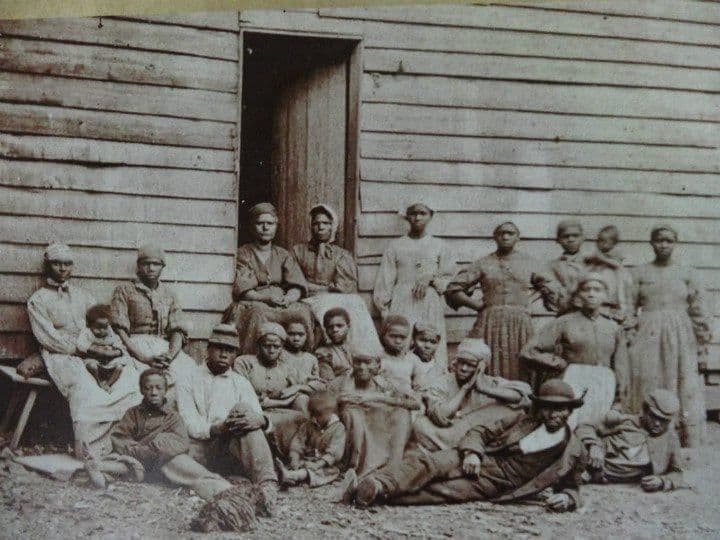

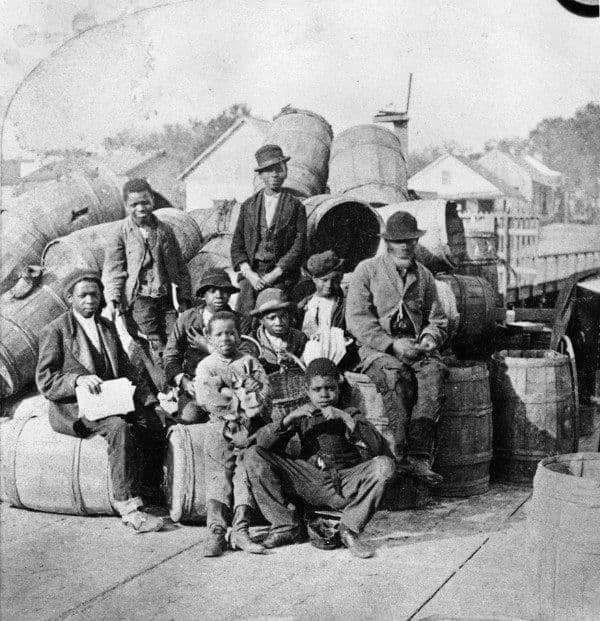

Let us learn more about the history of the land. Thomas Jefferson inherited the plot of land from his father. He had been 26 years old when he started to build the estate over 5,000 acres. Back then, the plantation served as a site for the cultivation of wheat and tobacco. Like other plantations in the country at the time, Monticello was involved in one of the darkest parts of American history: slavery. There was a lot of evidence showing how Jefferson relied on indentured labor to construct the house. Not only that, but there were also hundreds of slaves residing on the property and cultivating the ground. While it is hard to accept that such an important figure was a slave owner, the only way to move forward is to accept it and learn from their mistakes. In 2017, a discovery was made.

The Monticello Mystery

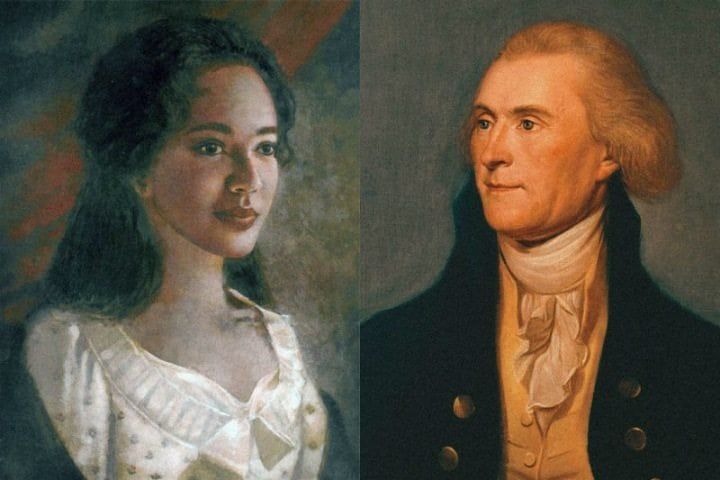

A Woman Called Sally Hemings

Sally Hemings was one of the many slaves who worked on Thomas Jefferson’s plantation. Even though this woman was a slave, her life seemed to have intertwined with Jefferson’s in a very unusual way. For this reason, historians were interested in the figure known as Sally Hemings for more than a century. There wasn’t much evidence that proved Sally Hemings was more than a victim of slavery. However, a discovery that took place almost 200 years after her death has provided new information regarding her life and all the connected events that formed the mystery of the Monticello estate.

A Woman Called Sally Hemings

They Learned More About Her

Many slaves were working on the plantation, and Sally Hemings was among them. She might have been a slave, but her life was intertwined with Thomas Jefferson in a rather unusual way. This is why so many historians have an interest in this woman. In the past, they did not find a lot of evidence to prove that she was more than just another victim of slavery. But nearly two hundred years after she passed away, experts stumbled into new information about her life. The Monticello estate is full of mysteries, and this discovery shed some light on the matter.

They Learned More About Her

The Truth About Her Family

She had a child by the name of Madison. However, he claimed that his mother was the half-sister of Martha, Thomas Jefferson’s wife. Sally Hemings was born to a planter and slave trader called John Wayles and a woman called Betty Hemings in 1773. He was the father of Martha Jefferson’s wife while she was born into slavery. At the time, the law said that the children of enslaved mothers would automatically go into slavery and work on plantations once they turn a certain age. Even though she was still a baby, she was taken to the Monticello estate and her mother and siblings. The records showed that they belonged to Martha Jefferson after inheriting them from her own father.

The Truth About Her Family

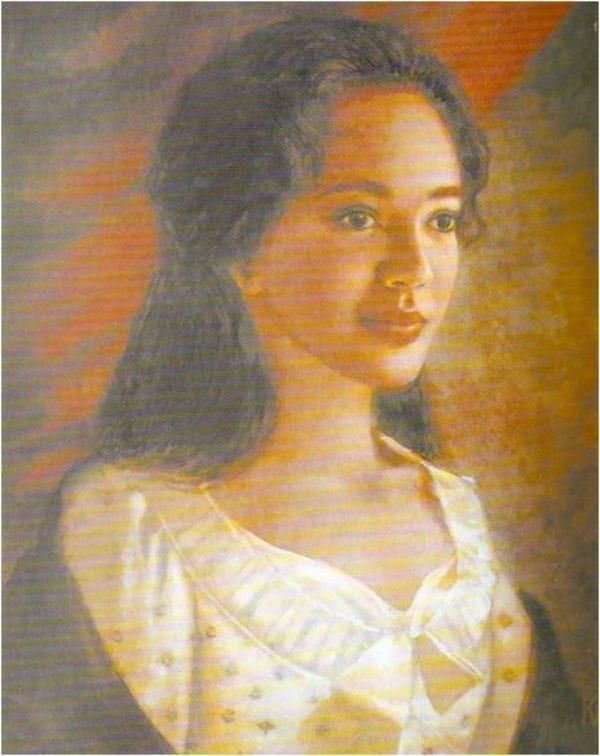

What She Looked Like

Sally Hemings has not enslaved her entire life. She was a slave from birth until the death of Jefferson in 1826. She got to spend the final 9 years of her life freely. Even though there is historical documentation available, they did not have many details about the time she spent in the Monticello estate. With the discoveries, we can now gather a couple of important clues that would help us understand this woman. We are sad to report that there is no painting of her or other visual proof of her appearance. Isaac Granger Jefferson was an enslaved blacksmith who gave one of the few descriptions of her. He said that Sally Hemings was “mighty near white… very handsome, long straight hair down her back.”

What She Looked Like

She Was A Lovely Woman

Even though there are no portraits of her, there are many descriptions that could give us an idea of her appearance. Thomas Jefferson Randolph, President Jefferson’s grandson, said that she was “light colored and decidedly good looking.” Trusted historians said that she served as a seamstress and chambermaid at the estate. Jefferson himself took very detailed records and notes about the finances and births on the past property. However, it looked like he did not write about this woman.

She Was A Lovely Woman

The Paris Trip Changed Her Life

Her life changed after she spent two years in Paris. At the time, she was only 14 years old! Sally Hemings was tasked to accompany Mary, the youngest daughter of Thomas Jefferson. They went to London and Paris because the future president had been the U.S. envoy to France back then. Hemings was not the only member of her family to go on this trip. You can find her brother James, who worked as the chef to the President, in the photo! Slavery was forbidden in France back then. But for some reason, Sally Hemings preferred to go back to the United States. Isn’t it interesting to hear that she wanted to return to her life as a slave in Monticello?

The Paris Trip Changed Her Life

During That Important Trip

At any rate, the Paris trip changed the course of her life. During the trip, Thomas Jefferson started an intimate relationship with the young girl. He had been a widower in his mid-40s at the time, while she was just 16 years old. Due to this turn of events, she fell pregnant. She left Europe for the United States in 1789. After that, she went on to give birth to six kids. Observers said they were considered the plantation owner’s children back then because they had an undeniable resemblance. While it was clear that Hemings and Jefferson had intimate relationships, no one could find writings about the affair.

During That Important Trip

A Lot Of Rumors

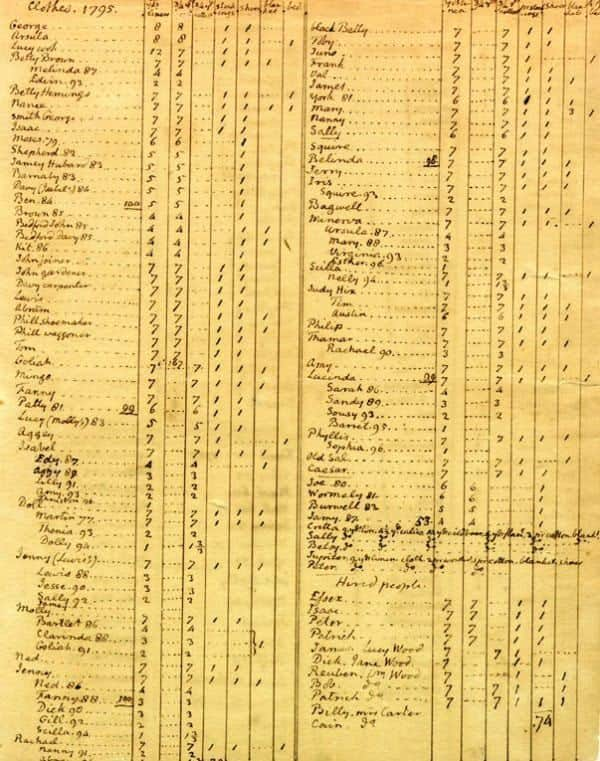

In 1802, the first written evidence of the affair finally came out. One of his opponents released a report that went on to be called the Jefferson-Hemings Controversy. The Jefferson family denied the claims that he was the father of her children. Despite this, Jefferson did not list down her children’s father’s name in the “Farm Book.” Sally Hemings gave birth to six children, but only four of them lived to adulthood. He eventually freed them all, which only fanned the rumors that he was the father. While he did this, the family kept denying the allegations. Some historians took their side for the 150 years that followed. However, the discoveries made all of us see the controversy in a new light.

A Lot Of Rumors

It Was A Match

The paternity of the children was an unresolved mystery for the longest time. We are glad that new advancements and developments have since allowed us to uncover the truth. Scientists managed to prove that Thomas Jefferson was truly the father of her children! The DNA testing happened in 1998 and proved that he was the father of one of her children. This made historians believe that he fathered all six of them. The genetic test showed a match between Sally Hemings’ youngest son Eston and the Jefferson male line. Two decades after the historical test, they learned even more things about the life of Sally Hemings. Are you ready to find out what they learned about this fascinating woman?

It Was A Match

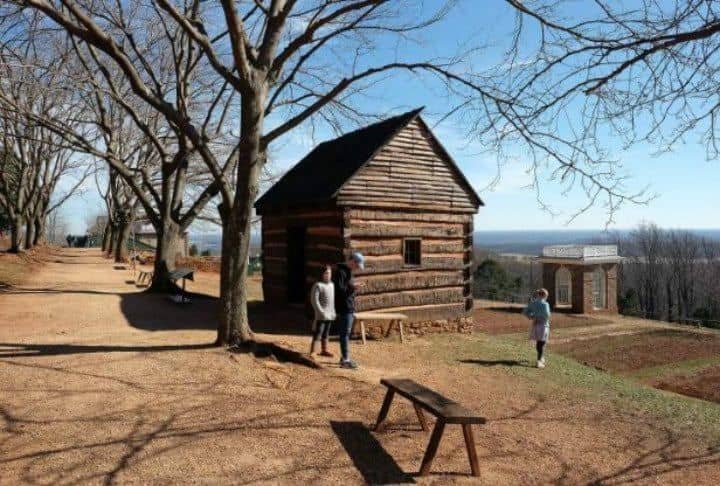

An Incredible Discovery

In 2017, the Monticello Plantation was slated for partial restoration. During the project, archaeologists launched excavations around the estate and found the missing piece to the plantation puzzle. For years, no one knew the truth. At long last, historians found the living quarters of Sally Hemings at last. To look at the original layout of the South Pavilion of the main house, archaeologists checked every nook and cranny. This was how they stumbled upon the historic find. It turns out that there was a hidden room that no one had seen for centuries. For the longest time, no one knew it was even there.

An Incredible Discovery

Her Hidden Room

The main house had a south wing that went through renovations a couple of times in the past. They took place both when Thomas Jefferson lived there and after that. The property saw a couple of transformations during the 20th century when it was turned into a museum. No one found the hidden room since it was right below a modern bathroom installed in 1941. After that, the bathroom in question was renovated in the ‘60s to expand to accommodate more visitors. Even though Monticello underwent a lot of construction work, the room stayed unnoticed for the longest time. But what exactly did they find when the cat was finally out of the bag?

Her Hidden Room

Where They Found The Clue

After they looked at the house’s past, historians found a document penned by one of Thomas Jefferson’s grandsons. The document said that the room was located on the south wing of the main house. Experts had no way to verify whether the information was correct. Despite this, they did realize that something could be hidden under the renovated bathroom. We are sure that it was an exciting find for them. However, they were surprised by what they found inside the chamber!

Where They Found The Clue

All These Interesting Discoveries

After some time, they launched the search. The team had to destroy the modern men’s bathroom and go through a lot of dirt. They eventually saw the remains of her 14-foot living space. To their surprise, it still had the original brick floor that dated back to the early 1800s. They continued to dig and found even more surprises this time around. They saw that the original brick fireplace and hearth were still there! Aside from the contents of the room, its actual location was also a mystery. They found it very interesting that it was adjacent to the bedroom of Thomas Jefferson himself! Was that a coincidence?

All These Interesting Discoveries

What It Meant

After they took a look at the new pieces of information, they now had more proof that Thomas Jefferson indeed fathered the kids of Sally Hemings. The proximity of her quarters to his room served as a huge clue. Let us not forget that there was also genetic evidence from the DNA test in the ‘90s. Together, historians concluded that they had the children together. Fraser Neiman, who serves as the director of archaeology at the estate, said, “This room is a real connection to the past. We are uncovering and discovering, and we’re finding many, many artifacts.” We are glad that they found the hidden room. It revealed more details about Sally Hemings, who arrived at Monticello as a slave.

What It Meant

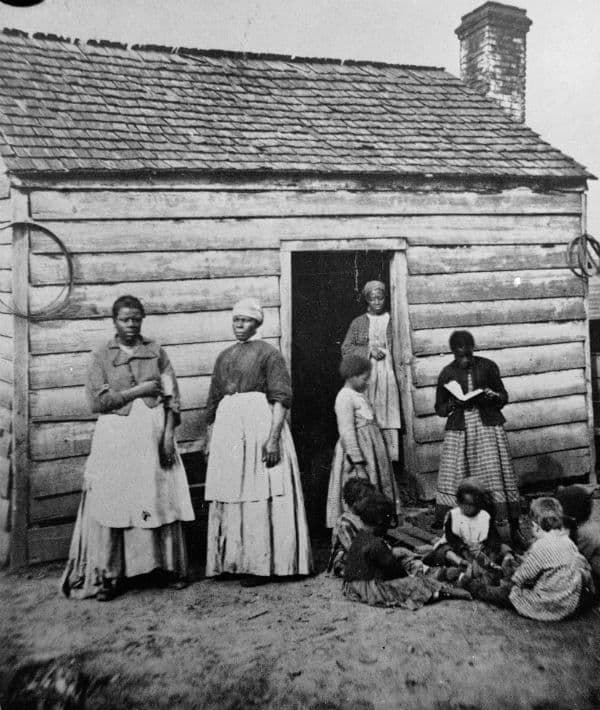

The Life Of Enslaved People

“This discovery gives us a sense of how enslaved people were living. Some of Sally’s children may have been born in this room,” said the director of the restoration of Monticello. Gardiner Hallock went on, “It’s important because it shows Sally as a human being — a mother, daughter, and sister — and brings out the relationships in her life.” With all the discoveries, historians finally figured out why Sally Hemings made the call to return to the United States after her time in Paris. Thomas Jefferson must have promised her to free the kids once they were adults. Interestingly, the Hemings family had been the only family that he freed in his lifetime. He freed certain individuals but never an entire family.

The Life Of Enslaved People

Compared To Others

Aside from proving that he fathered the kids of an enslaved woman, the discovery of the room shed light on her lifestyle. Sally Hemings indeed had a higher standard of living than the rest of the slaves at the Monticello estate. While she had certain privileges, she stayed a slave and kept working at the property like the others. It was true that her room was located adjacent to the private quarters of Thomas Jefferson. It was not a luxurious place. They saw that it did not have windows, so there is a good chance that it was dark and uncomfortable. A group believes the bathroom was built on top of the room to cover up its existence. They think that its construction was offensive to her legacy.

Compared To Others

The Restoration Of The Room

The Monticello historians went on to work on the restoration of her room. In 2018, they opened it to the public at last. They decided to put it up for display, complete with artifacts and furniture from that period. Among other things, there were bone toothbrushes and ceramics there. The project cost them 35 million dollars and was called the Mountaintop Project. It was made to bring in more transparency on the history of the estate. The project aimed to share the story of those who lived and worked at the plantation. It also focused on the story of the extraordinary Hemings family.

The Restoration Of The Room

The First Proof In History

“For the first time at Monticello, we have a physical space dedicated to Sally Hemings and her life,” Mia Magruder Dammann said. She is the spokeswoman for Monticello. She went on, “It’s significant because it connects the entire African American arch at Monticello.” With the discovery of the room, we got to learn more about Sally Hemings. It also helped us get a better understanding of the life of the enslaved workers at Monticello. This helped historians get a better idea of the kind of man Thomas Jefferson was.

The First Proof In History

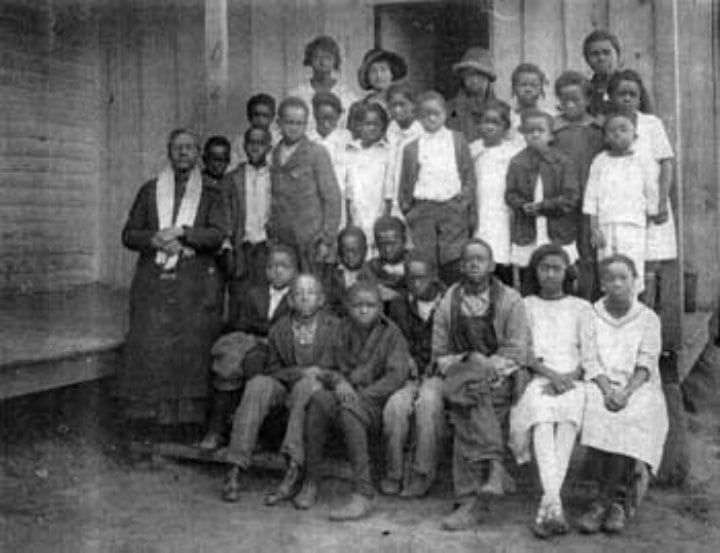

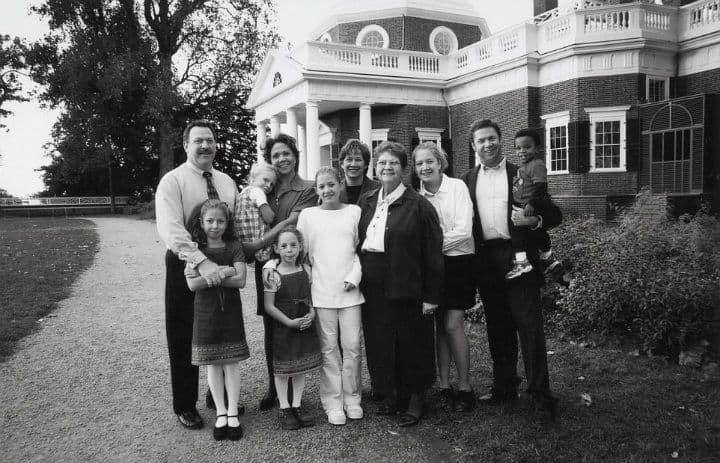

Outside Of The Mystery

Niya Bates is a historian who said that discovering the secret room for Sally Hemings would “portray her outside of the mystery.” The new exhibit helped humanize this important woman, whose life has always been surrounded by gossip for the longest time. Bates continued, “She was a mother, a sister, an ancestor for her descendants (pictured), and [the room’s presentation] will really just shape her as a person and give her a presence outside of the wonder of their relationship.”

Outside Of The Mystery

In Memory Of Sally Hemings

The new findings have changed the way that we look at Monticello. This time around, the focus is on Sally Hemings. After all, she is the subject of the fascinating exhibitions at the property. A retired historian named Lucia “Cinder” Stanton started working at the plantation in 1968. She said that tours did not even mention the name of Sally Hemings in those days. We are sure that this is going to change. In the past, there was much to say about her and her family. In 1993, curators began to include the stories of the slaves in the exhibitions on tours as part of the 250th anniversary of Thomas Jefferson’s birthday. Even so, it took some time before the descendants of the slaves got to drop by.

In Memory Of Sally Hemings

A Project Called Mulberry Row

Aside from Sally Hemings, they also put the spotlight on other enslaved people. A new project was launched at Monticello in 2015. It showed the stories of the slaves at the plantation. The restaurant Mulberry Row opened its doors and displayed the street dwellings’ reconstruction on the central plantation. This was where the enslaved workers resided. The row showed over twenty structures from 1770 to 1831. The restaurant invited than a hundred descendants of the slaves to participate in the tree-planting memorial. Mind you. This was simply the first of many planned commemorative events.

A Project Called Mulberry Row

Her Life In Focus

Aside from Mulberry Row, the curators also plan to put more focus on Sally Hemings. They plan to bring her room and life story to the spotlight. Among other things, they want to offer a complete account of what she went through at the Monticello estate. Of course, they plan to talk about her relationship with Thomas Jefferson and other people as well. The recent discovery helped them solve the mystery of her life after such a long time. We are curious to see what her descendants think about the recent findings.

Her Life In Focus

What Their Descendants Had To Say

Gayle Jessup White is the great-great-great-great niece of Sally Hemings and a Community Engagement Officer at Monticello. She shared, “As an African American descendant, I have mixed feelings – Thomas Jefferson was a slaveholder.” Despite this, she said that she appreciates all the work by her colleagues. “But for too long, our history has been ignored,” she said. “Some people still don’t want to admit that the Civil War was fought over slavery. We need to face history head-on and face the blemish of slavery, and that’s what we’re doing at Monticello.” More people feel the same way.

What Their Descendants Had To Say

It Got Mixed Reactions

On top of that, she said that people tend to feel conflicted about Monticello being a part of African-Americans’ history. “I find that some people are receptive to the message, and some are resistant,” she shared. “But our message is that we want the underserved communities and communities of color to become partners with us.” She went on, “Anecdotally, we have seen an uptick in African Americans visiting Monticello, so I know we’re making progress.”

It Got Mixed Reactions

There Are Questions Still Unanswered

Even though the room was a truly groundbreaking discovery, it did not answer all the holes in the estate’s history. Thomas Jefferson indeed had a log of the slaves on the plantation, but there were not many individual portraits of the enslaved people who worked there. Their descendants lived at the Monticello estate and revealed more information about what it was like back then. This allowed us to take a glimpse of things that had not been written about in the past.

There Are Questions Still Unanswered

The Descendants Of Sally Hemings

Another source of information about Sally Hemings would be her descendants. They helped create a family tree for their lineage. They were linked to Thomas Jefferson, so we can also combine it with that of his descendants. In 2008, a historian called Annette Gordon-Reed released a book called “The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family.” In the book, the author talked about enslaved people’s lives and traced the family’s history through the years. She went through their farm logs, diaries, legal records, and more. In the end, her efforts led to an astonishing find.

The Descendants Of Sally Hemings

What Happened To Her Children

Sally Hemings had four kids who lived to turn into adults. They were Eston, Beverly, Madison, and Harriet. Every one of them spent all their lives in the North, with the sole exception of Madison. He wrote a memoir that shed more light on his siblings. His writing is generally thought to be a reliable account. He said that Harriet and Beverley both got married to affluent men in Washington DC’s white society. Meanwhile, the two men married free women of color in Charlottesville. However, Eston was the only one who changed his surname to Jefferson to acknowledge his paternity.

What Happened To Her Children

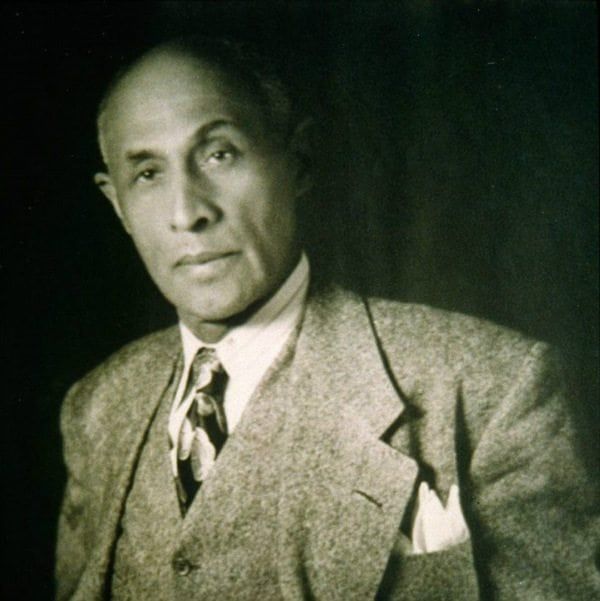

Madison And Eston Hemings

Both Madison and Eston saw success in their careers and fathered multiple kids. Some of them went on to fight in the Civil War for the Union. Their children went on to have children of their own and so on. Interestingly, a couple of generations after the Jefferson presidency, his great-grandson called Frederick Madison Roberts, made history as the first elected person of black ancestry to hold a public office position on the West Coast. He was in the California State Assembly for two decades.

Madison And Eston Hemings

They Collected Accounts And Anecdotes

In 1993, the Monticello historians talked to more than 200 people to learn more about the subject. The interviews made up a key part of an oral history project. Its goal was to collect the personal accounts of the people who resided and worked at the Monticello plantation. In 2016, the estate also hosted a summit and the National Endowment for the Humanities and the University of Virginia. A couple of descendants of the families who lived there went to the event. It was called “Memory, Mourning, Mobilization: Legacies of Slavery and Freedom in America.”

They Collected Accounts And Anecdotes

A Deeper Understanding

On the other hand, the stories given on Monticello museum tours greatly changed to offer a more accurate account of the property’s history. Tom Nash, one of the manor’s guides, talked about its history in a pretty candid way. “This is a spectacular view from this mountaintop,” he shared with the visitors. “But not for the enslaved people who worked these fields. This was a tough job, and some of them — even young boys 10 to 16 years old —felt the whip.” He is clearly not afraid to tell as it was.

A Deeper Understanding

The Visitors Were Intrigued

After he shared this, the curious visitors had several questions for him. Among other things, they asked, “Why did some slaves want to pass for white when they were freed?” and “Why did Jefferson own slaves and write that all men are created equal?” In response to these, he replied, “Working in the fields was not a happy time. There were long days on the plantation.” He went on, “Enslaved people worked from sunup to sundown six days a week. There was no such thing as a good slave owner.”

The Visitors Were Intrigued

Monticello At The Moment

We do not doubt that people will continue to talk about the Monticello controversy in the future. Despite this, the estate hosted a fantastic celebration to mark its 55th Independence Day in July 2017. More than 70 people from 30 countries went to the event and received citizenship via naturalization. Together with the rest of the world, the United States acknowledges the stories and the contributions of these people will not be forgotten. Their freedom might have been restricted during their lifetime, so the least we can do is to honor their memory now.

Monticello At The Moment

Not The Only Slave Owner President

Many people like to point out how ironic that Thomas Jefferson was a slave owner when he declared that “All Men Were Created Equal.” This is also true for other presidents of the United States. Many of the earlier ones owned slaves as well. Historians say that a total of twelve of them had slaves when they were still alive. Not only that, but eight of those had slaves when they were in power as well. While the United States was allegedly founded on quality, we can see that it is not really the case.

Not The Only Slave Owner President

George Washington Also Had Slaves

Among the presidents who were slave owners, something sets George Washington apart. After all, no one else freed personal slaves. In his will, he asked to give them their freedom upon his death. Martha, his wife, free over a hundred slaves after he passed away for this very reason.

George Washington Also Had Slaves

Those Who Did Not

Did you know which president was the first one to live in the White House? This honor went to none other than John Adams. He had “moderate” views on slavery and therefore did not own slaves. Despite this, slave labor was still used in the construction of the presidential residence. John Quincy Adams, his son, went on to become the sixth president of the United States. Like his father, he did not have slaves either. As a matter of fact, he began to oppose slavery years after he left office.

Those Who Did Not

You Do Not Learn This In School

We hope that you have since learned more about Thomas Jefferson. We sincerely doubt that you read about these things in your history textbooks. While he called slavery an “assemblage of horrors,” he was a slave owner himself. Sadly, he was not the last president to be one. Who are the others? Well, they include Andrew Jackson, James Madison, and James Monroe. Martin Van Buren, the eighth president of the country, owned no more than one single slave. He joined the opposition to slavery later on too.

You Do Not Learn This In School

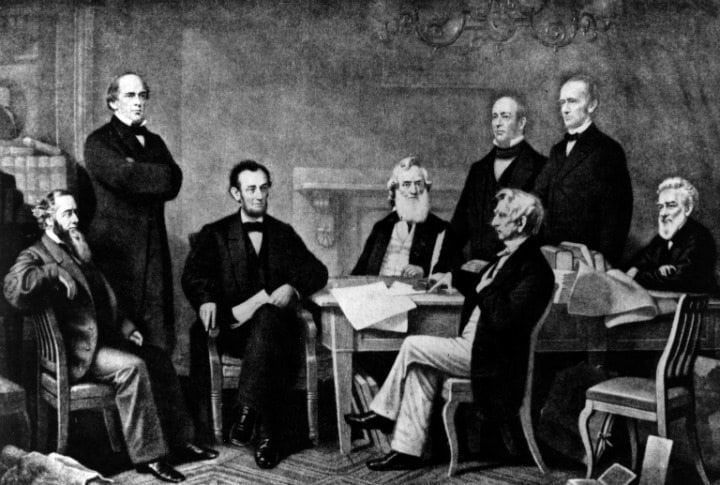

The Last Presidents To Be Slave Owners

William Henry Harrison might have inherited a couple of slaves, but he did not have slaves during his presidency. This was quite significant as he was in office for 31 years. On the other hand, we have John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and James Polk. They all owned slaves during their terms. Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant were the last presidents to have slaves. Abraham Lincoln, the 16the President of the United States, signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. It led to the freedom of more than 3 million slaves. Two years later, slavery was finally abolished when the 13th Amendment was put in place.

The Last Presidents To Be Slave Owners

Burwell Colbert

Burwell Colbert was an unpaid migrant worker at Monticello from 1783 to 1862. Betty Brown was his mother, and Elizabeth Hemings was his grandmother. Colbert started working at the Mulberry Row nail shop when he was ten years old and later learned painting and window glazing. Painting the balusters and Chinese railing on the roof and the landau carriage designed by his uncle John Hemmings and cousin Joseph Fossett were among his accomplishments.

Burwell Colbert

Elizabeth Hemings

Elizabeth (Betty) Hemings was the matron of a powerful and large family that accounted for a third of Monticello’s population, making them the largest family ever to live there. The Hemings and Jefferson families were forever connected by bonds of slavery and kinship, reflecting the complexities of enslaved people’s relationships with their owners. The children and descendants of Elizabeth Hemings held the most powerful household and trades positions on the mountain. Many of her children were able to contract themselves out and retain their earnings, which was a rare occurrence among Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved.

Elizabeth Hemings

Martin Hemings

Martin Hemings was Elizabeth Hemings’ oppressed son. He was born and grew up in John Wayles’ plantation house, The Forest. Martin was sent to Monticello after Wayles’ death in 1773 and served as a butler for Thomas Jefferson. According to family tradition, when Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s troops approached Monticello in 1781, Martin Hemings was in charge of hiding the Jeffersons’ family silver. 1 Hemings “desired” that Jefferson sell him to a different leader after an unexplained disagreement, and Jefferson agreed.

Martin Hemings

Mary Hemings Bell

Elizabeth Hemings’ oldest known daughter was Mary Hemings Bell. Bell was brought to Monticello with her family after the estate of Martha Jefferson’s father, John Wayles, was divided in 1774, where she worked as an enslaved household servant and seamstress. Mary Hemings Bell gave birth to six children between 1772 and 1783, some of whom were sold away from her and others who lived in freedom.

Mary Hemings Bell

Robert Hemings

Elizabeth Hemings and John Wayles, Thomas Jefferson’s father-in-law and Elizabeth Hemings’ master before Jefferson inherited her, had a son named Robert Hemings. The first of their six children, Robert Hemings, was born in 1762. Hemings appears to have been Jefferson’s enslaved body servant by at least 1775, a title previously held by Jupiter Evans. Jefferson accompanied Hemings to Philadelphia in 1775 and 1776, and he was described as a “bright mulatto.” Dr. William Shippen, who had inoculated Jefferson almost a decade before, inoculated him against smallpox in 1775.

Robert Hemings

Sally Hemings

Sally Hemings is a well-known African American woman in American history. Her name has been related to Thomas Jefferson as his “concubine” for more than 200 years, obscuring the truth of her life and identity. Sally Hemings, unlike many other enslaved women, was willing to bargain with her master. The 16-year-old decided to return to Monticello’s enslavement in exchange for “extraordinary rights” for herself and protection for her unborn children when she was free in Paris.

Sally Hemings

Edith Fossett

Edith Hern Fossett worked as the enslaved head chef at Monticello after Thomas Jefferson’s retirement. She taught French cooking at the President’s House in Washington, D.C. The meals at Monticello were “in half Virginian, half French style, in good taste and abundance,” according to Daniel Webster, who was referring to her cooking. In 1802, Thomas Jefferson determined that fifteen-year-old Fossett should train as a cook at the White House under Honoré Julien, George Washington’s chef.

Edith Fossett

Joseph Fossett

Joseph Fossett was the son of Elizabeth Hemings’ eldest daughter, Mary Hemings Bell. He was a professional blacksmith who “could do anything with steel or iron that was required.” Though some of Fossett’s descendants claim Thomas Jefferson as their paternal grandfather, Joseph’s surname indicates a different parentage. A white carpenter named William Fosset worked at Monticello in the years leading up to Fossett’s birth. When Jefferson was governor of Virginia, Fossett’s mother and other enslaved housekeepers lived in Richmond.

Joseph Fossett

Peter Fossett

Peter Farley Fossett was a part of Monticello’s enslaved population. He later became a successful caterer in Ohio, a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and pastor of First Baptist Church, Cumminsville, where he worked for 32 years after gaining independence at 35 with the support of his family. Peter Fossett remembered the comparison between Monticello and his new owner’s plantation, Colonel John Jones, in his reminiscences, published in 1898, where he was threatened with a whipping if ever caught with a book in his hand.

Peter Fossett

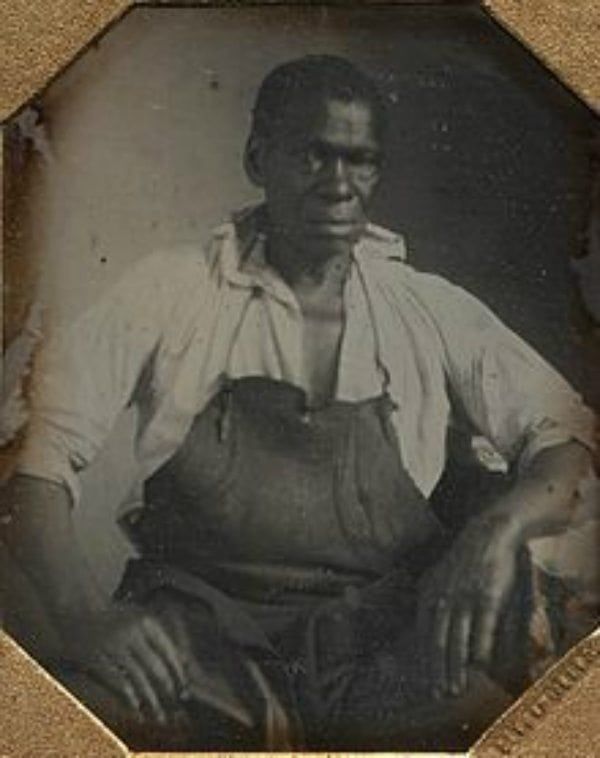

Isaac Granger Jefferson

At Monticello, Isaac Granger Jefferson worked as an enslaved tinsmith and blacksmith. Granger’s short memoir, published in the 1840s by an interviewer, includes significant and interesting details about Monticello and the people who lived there and major historical events that he experienced. Granger was the third son of two influential members of Monticello’s enslaved labor force. His father, George Granger, rose from foreman of labor to Monticello’s overseer in 1797 — the first enslaved person to hold that position — and was paid £20 a year.

Isaac Granger Jefferson

Harriet Hemings

Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson had only one daughter, Harriet Hemings. She grew up in Monticello with her three brothers and a huge extended family. Hemings, like her mother, was enslaved by her father and employed as a wool spinner in the textile workshop. When she was twenty-one years old in 1822, she “ran away” with Jefferson’s experience and moved to Washington, D.C., where she began a family and entered white society as a free woman.

Harriet Hemings

James Hemings

Even though James Hemings was a chef de cuisine with a Parisian education, he was born into slavery and spent most of his life there. He negotiated legal manumission and started his life as a free man when he was thirty years old. He traveled and worked as a cook, but due to his tragic and unexpected death at the age of thirty-six, his life and career in freedom were cut short.

James Hemings

John Hemings

At Monticello, John Hemmings worked as a contracted joiner. According to legend, he was the son of Betty Hemings, an enslaved woman, and Joseph Neilson, one of Thomas Jefferson’s white house joiners in the 1770s. Hemmings began his career as an “out-carpenter,” chopping down trees and hewing logs, constructing fences and barns, and assisting in constructing Mulberry Row’s log slave dwellings.

John Hemmings

Peter Hemings

Peter Hemings was the ninth child of Elizabeth Hemings, the matriarch of the Hemings family at Monticello, and her fifth child with her master at the time, John Wayles, Thomas Jefferson’s father-in-law. Peter Hemings learned how to brew and took over the brewing and malting processes at Monticello in 1813. Hemings mastered brewing “completed successfully,” according to Jefferson, and possessed “great intellect and vigilance, all of which are indispensable.”

Peter Hemings

Madison Hemings

Madison Hemings was Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson’s second surviving son. His uncle, John Hemmings, showed Madison Hemings how to deal with wood. Owing to the terms of Thomas Jefferson’s will, he was set free in 1827. Hemings and his brother Eston left Monticello to live in Charlottesville with their mum, Sally Hemings. They bought a lot and designed a two-story brick and wood house together.

Madison Hemings

Eston Hemings

Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson had a son named Eston Hemings. Eston Hemings learned the woodworking trade from his uncle, John Hemmings, and was set free in 1827 by Thomas Jefferson’s will. He and his brother Madison left Monticello to live with their mother, Sally Hemings, in Charlottesville. They bought a lot and designed a two-story brick and wood house together.

Eston Hemings

James Hubbard

James Hubbard, also known as Jame or Jamey by Thomas Jefferson, was James Hubbard, an enslaved farm labor foreman at Jefferson’s Poplar Forest plantation, and his wife, Cate. Then eleven years old, Jefferson had Hubbard taken to Monticello to serve in the new Mulberry Row nailery in 1794. He shared a log dwelling at the top of the mountain with Phill the wagoner and his companion, Molly; his younger brother Philip (“Phill”) accompanied him two years later. Hubbard tried two times as an adult to escape Monticello.

James Hubbard

Robert Hughes

Robert Hughes (1824-1895) was linked to the Hemings and Granger families, two influential enslaved families at Monticello. At Monticello, Robert Hughes was born. He was enslaved at Edgehill, the plantation of Thomas Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, with his mother and other siblings before the Civil War ended. Hughes, a blacksmith, bought over a hundred acres of Albemarle County property during the battle. He was the founding minister of Union Run Baptist Church, where he led for three decades near Charlottesville, Virginia.

Robert Hughes

Wormley Hughes

Wormley Hughes, the son of Betty Brown and Elizabeth Hemings’ grandson, was born in March 1781 at Monticello. He was an accomplished gardener responsible for much of the landscaping improvements at Monticello and Jefferson’s nearby estates. He married Ursula Granger Hughes, an enslaved cook at Monticello, with whom he had thirteen children. After Jefferson’s passing, he was granted informal independence by the Jefferson family. Hughes continued to work with Monticello family members. In the summer of 1858, he passed away.

Wormley Hughes

Minerva Granger

Minerva Granger, the daughter of Squire and Belinda, who belonged to Jane Randolph Jefferson at the time, was born in Shadwell in September 1771. Minerva and her family were relocated to Monticello two years later after the property was transferred to Thomas Jefferson’s possession. She would live most of her time at Monticello and would be bought by Jefferson’s grandson after his death.

Minerva Granger